The law of torts functions as a tool to encourage individuals to act responsibly and to respect the rights and interests of others. It achieves this by safeguarding certain recognized interests and enabling those whose interests are unjustly violated to seek compensation from those responsible for such breaches.

The term “interest” refers to any claim, desire, or goal that a person or a group seeks to fulfill and which, consequently, should be acknowledged within the structure of a civilized society. However, not every personal wish or loss warrants protection, nor does every instance of loss entitle a person to recover damages from the person causing it. Because of this, the law identifies which interests justify protection and mediates conflicts between competing protected interests.

When the law protects an interest, it creates a corresponding legal right, which comes paired with a corresponding legal duty on others. Some legal rights are considered absolute, meaning any violation of them is presumed to have caused legal harm. Other rights are not absolute, and in such cases, the law requires proof of actual harm before recognizing a cause for legal action.

A wrongful action is one that infringes a legal right. However, not all wrongful acts amount to a tort. For an act to constitute a tort or a civil injury:

- There must be a wrongful act by an individual.

- This act must lead to legal harm or actual damage.

- The act must be of a kind that entitles the affected party to a legal remedy, usually through an action to recover damages.

Wrongful Act

For an act to give rise to a claim in tort, it must be legally wrongful with respect to the claimant. This means it must harm or prejudice a legal right belonging to the person complaining—not simply cause them harm in a general sense.

Even actions that seem innocent on the surface may be considered torts if they violate someone else’s legal rights. For instance, constructing something on your own property is generally lawful, but if your neighbor has earned the right (through long-term use) to receive uninterrupted sunlight across your land, then building a structure that significantly blocks that light infringes their right. In this case, the construction is not just damaging but is considered legally wrongful.

The key test for whether an act or omission is legally wrongful is whether it negatively affects another person’s legal right.

What is a Legal Right?

A legal right can be described as a power or entitlement that a specific person (or group) has under the law, which entitles them to expect certain behavior from others who owe corresponding duties. Legal rights can be categorized as:

- Private Rights: These are rights particular to an individual, protected against interference by others. Examples include:

- Rights protecting reputation

- Rights safeguarding personal safety and freedom

- Rights relating to property (which can include both tangible and intangible interests, and the ancillary rights necessary to use and defend one’s property)

- Public Rights: These are rights held by all members of a community or state. If a public right is violated through unlawful conduct, an individual generally cannot sue unless they have suffered unique, direct, and considerable harm beyond what the general public has experienced. Normally, such infringements are dealt with through criminal proceedings, preventing the courts from being overloaded with lawsuits by all affected individuals.

Duties and Corresponding Rights

Every right recognized by law is paired with a duty. These duties can require a person to take action or to refrain from specific actions. For example, if someone has a right of way, the owner of the land must not put up barriers; similarly, if there is a legal right to light, a neighbor may be legally obliged not to erect structures that block it.

The law of torts centers on the duty to avoid deliberate harm, to respect others’ property, and to act carefully so as not to negligently cause injury.

Basis for Liability

Liability for tortious conduct arises when an act:

- Violates someone’s private legal right, or

- Constitutes a breach of a legal duty imposed by law.

Damage in Tort Law

“Damage” in legal terms refers to the injury, harm, or loss that a person suffers because of another’s wrongful conduct. The monetary award that the court grants to compensate the affected individual for this harm is called “damages.”

Absolute vs. Qualified Rights

Legal rights are broadly divided into:

- Absolute rights, where any violation is presumed by law to have caused damage, even if there is no actual loss suffered. This presumed harm is called “legal damage,” and infringement of such rights is actionable on its own, without the need to prove actual loss.

- Qualified rights, where no such presumption exists. Here, the complainant must show real, quantifiable harm to claim relief. That means an action under tort law in these cases requires evidence of actual or “special” damage.

Two Key Legal Maxims

These maxims clarify when a legal claim arises:

- Injuria sine damno: This refers to the breach of an absolute right without any real or tangible loss. The mere violation of the right is enough for a court action, even if it does not result in any loss of money or property. Classic examples include trespass, assault, battery, libel, and false imprisonment—these are actionable even when no clear loss is incurred. Courts will award at least nominal damages in such situations.

- Damnum sine injuria: This refers to actual losses—whether financial, physical comfort, or reputation—that occur without the violation of a legal right. In such cases, even if harm has been suffered, no lawsuit can be maintained because there is no unlawful act recognized by law. For example, if a competitor opens a rival business and your profits decrease, you cannot sue simply for your loss.

Illustrations

- Turning someone away from voting wrongfully is actionable, even if it caused no real outcome or loss, because it infringes the legal right to vote.

- A bank refusing to honor a check can lead to legal action, even if no financial damage is shown, provided legal rights are breached.

- On the other hand, setting up a competing business, using a similar house name, or causing loss through lawful means (like extracting water from your property or erecting a building that accidently damages a neighbor’s wall when no legal right is infringed) are not actionable in tort if no specific right has been violated.

Actual Damage Required (Qualified Rights)

Certain torts require actual harm as part of the claim. These include, but are not limited to:

- Loss of support between neighboring landowners

- Seduction

- Deceit and fraud

- Some forms of slander

- Menace and intimidation

- Negligence

- Certain nuisances (like property damage)

- Inducing another to break a contract

Practical Points

- The existence of a moral or ethical wrong alone does not guarantee a legal remedy unless a recognized right is breached.

- Conversely, a violation of an absolute legal right is enough to bring an action, even if no real damage is evident.

- Where only a threat of infringement exists, a person may seek preventive remedies such as a declaration or an injunction under special legal provisions.

Summary Table:

| Category | Example(s) | Actionable Without Proof of Damage? |

|---|---|---|

| Absolute right | Trespass, assault, libel | Yes |

| Qualified right | Negligence, nuisance, deceit | No – must show actual damage |

| Damnum sine injuria | Business competition losses | Not actionable |

| Injuria sine damno | Voting rights breach, trespass | Yes – actionable per se |

In all, for an action to succeed in tort law, the claimant must either show the violation of an absolute legal right or demonstrate actual loss resulting from the breach of a qualified right. If neither is present, no claim can be maintained, regardless of the harm suffered.

Important articles

-

January 22, 2026

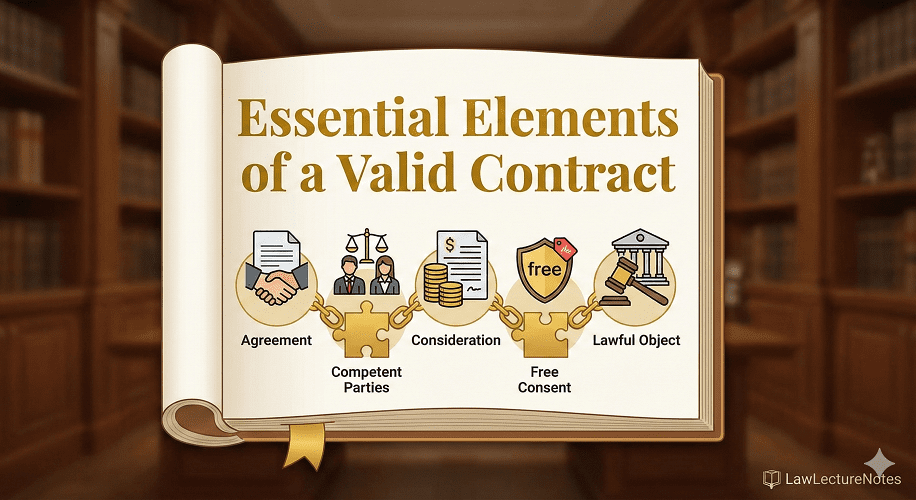

January 22, 2026The Blueprint of a Binding Deal: Overview of Essential Elements of a Valid Contract

Spread the love In the world of commerce, thousands of promises are made every day. But when does a casual promise transform into a legally bindingRead more -

January 24, 2026

January 24, 2026What Agreements Are Contracts? Decodifying Section 10

Spread the love In our daily lives, we make countless agreements. We agree to meet friends for coffee, agree to attend a family wedding, or agreeRead more -

January 24, 2026

January 24, 2026Conclusion: The Importance of Chapter 1 in Contract Law

Spread the love We have now journeyed through the basics of the Indian Contract Act, 1872—from the first spark of an Offer to the binding sealRead more